The Compromise of the Skeptic: An Analysis of The Black Swan

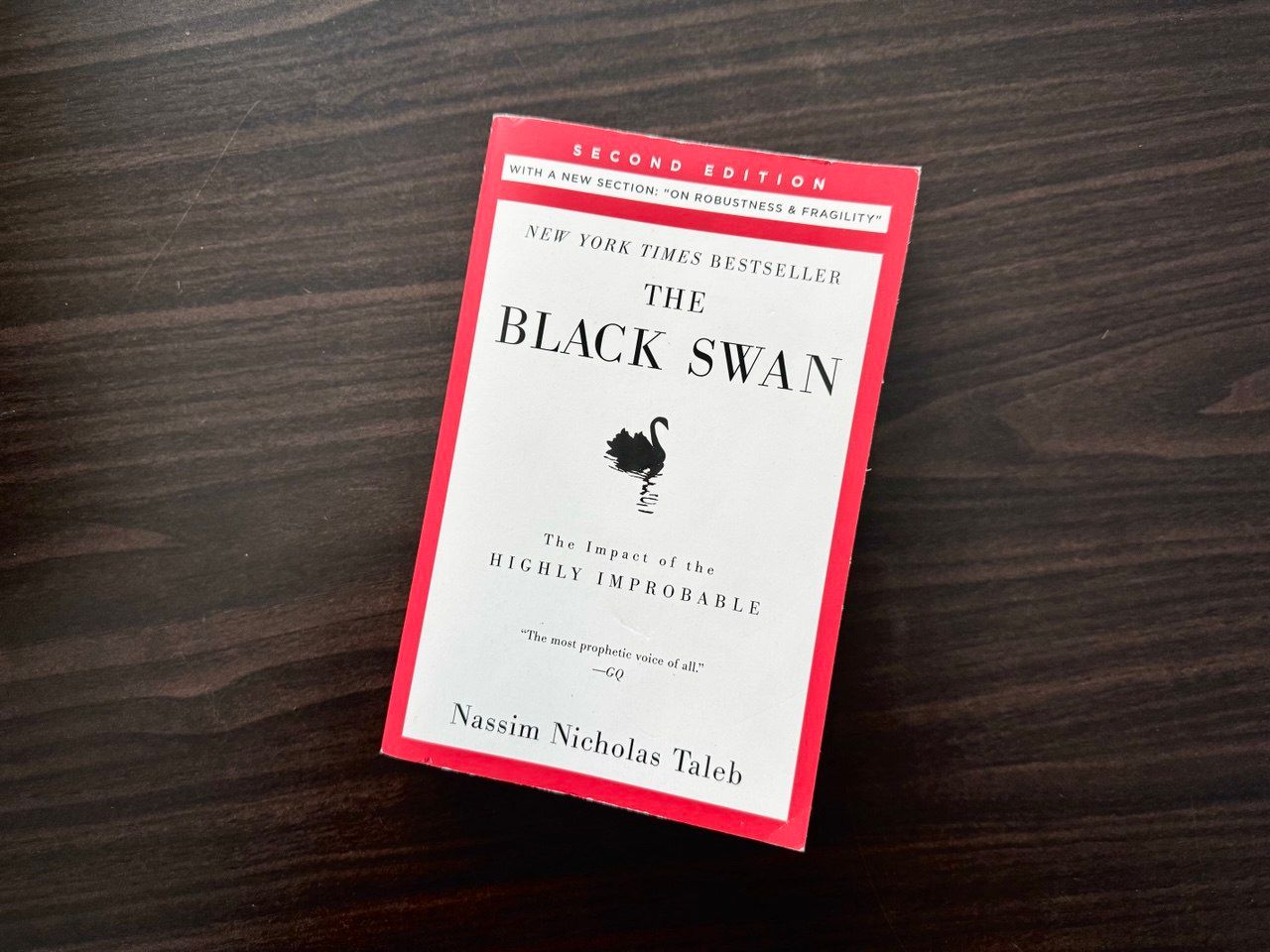

One of the most mind-bending books I've been reading is The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable by Nassim Nicholas Taleb. I had decided to start reading it due to its iconic stature in 21st-century non-fiction; it seems as if every other book references some aspect of The Black Swan, or at least another one of NNT's books. While I was an initially skeptical about its merits, the book won me over with time, and raised many valuable insights into probability and the way we perceive it. What particularly stuck out to me was NNT's idea of the narrative fallacy. I want to delver deeper into this and its limitations, and how it can help inform a general strategy towards life.

But first, we need to establish what a Black Swan is. A Black Swan is an event of low probability that has high impact, for which a hidden causal relationship is usually surmised in hindsight. A book becoming highly successful is a Black Swan, as is an unexpected crash in the markets. Some professions are reliant on positive Black Swans, such as writing or science, while other professions offer a more stable reward, such as baking or accounting. Most importantly, we tend to be blind to Black Swans despite their disproportionate impact, and this books has a corresponding epistemic goal: to inform readers of what Black Swans are so that they can more correctly perceive the role and likelihood of uncertain events, and turn at least a few of the swans gray.

Epistemic Arrogance & the Narrative Fallacy

I want to start by sharing the line that made me read on in the first place.

What I saw was that in one of the most prestigious business schools in the world, in the most potent country in the history of the world, the executives of the most powerful corporations were coming to describe what they did for a living, and it was possible that they too did not know what was going on. As a matter of fact, in my mind it was far more than a possibility. I felt in my spine the weight of the epistemic arrogance of the human race. (Chapter 1, pg. 17)

Hayek's Knowledge Problem

This controversial take sets the tone of the whole book, where NNT bemoans the extent of epistemic arrogance within large institutions. This focus on the difference between what people think they know and what people actually know is a much-needed reminder of the role that free markets play. Indeed, the footnote to the above quote extolled the free-market system as being able to work things out in spite of epistemic arrogance. This indirect reference to F. A. Hayek's spontaneous order as a natural panacea to the knowledge problem is made explicit in the Chapter 11 section They Still Ignore Hayek, where NNT uses Hayek's knowledge problem to criticize the forecasts and projections made by governments and large corporations.

The knowledge problem refers to the idea that knowledge is decentralized among individuals; no single person has enough knowledge to be able to centrally plan the economy. Instead, only through the spontaneous order of the free markets can resources be allocated efficiently. NNT takes this idea and expands it to include non-economic decisions as well. I find there to be a nugget of wisdom here: there is a practically infinite amount of knowledge available, and this makes it impossible to really predict what can happen next, or really know the causes of past events.

Compared with the totality of knowledge which is continually utilized in the evolution of a dynamic civilization, the difference between the knowledge that the wisest and that which the most ignorant individual can deliberately employ is comparatively insignificant.

— Friedrich A. Hayek (link)

Naturally, an application of this is a baseline distrust for institutional actors (or "experts") who, with the inability to know everything, instead make an informed guess as to what's going on, a narrative that provides epistemic comfort.

The Narrative Fallacy and the Narrative Necessity

In the glossary, the narrative fallacy is defined as "our need to fit a story or pattern to a series of connected or disconnected facts". Mathematically speaking, the knowledge of the narrative fallacy recognizes the limits of our interpretation when we perform dimensionality reduction. In fact, NNT contends that dimensionality reduction is what we perform daily, even outside a mathematical setting; we simplify details in order to come up with narratives, especially by only looking for evidence that supports our initial beliefs (confirmation bias) or by ignoring the "silent evidence" (the businesses that have failed, the good authors that have never received success, etc.).

While I agree that there are limits to our interpretation of events, narratives do have their essential role in our understanding of the world. Let's look at this from the perspective of modern Economics, which NNT repeatedly criticizes.

Blind experimentation (as an empirical process) can only get us so far, and there are many things that cannot be experimented on. One of the things I've learnt as an Economics major is that idea that models are needed because, in many cases, we can't experiment on an actual economy in an ethical manner. However, even if we could run experiments on the economy, I believe the applicability of the results is limited due to the assumptions made, and NNT's idea of the narrative fallacy applies here quite nicely. (The same argument applies to long-term analyses of existing economies.)

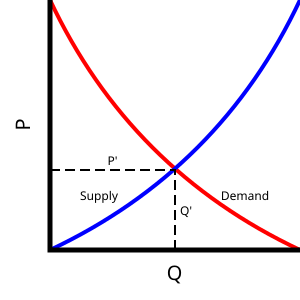

Indeed, taking a page out of notable Austrian School economist Ludwig von Mises' book, an empirical approach to Economics has its limits, and the focus should instead be on rationalism. However, rationally-derived models are subject to the same narrative fallacy, by offering an overly simplistic view of economics, in spite of the theoretical foundations that underpin them. In fact, it seems as if the best use of models is pedagogical; economics with fewer dimensions offers the more mathematically inclined with a better intuition of economics concepts. NNT uses the term "Locke's madman" in this scenario, which refers to the phenomenon where extensive work is done based on faulty assumptions. In the book, he applies it to Modern Portfolio Theory and the Black-Scholes-Merton Equation, but it can generalized to most economic models.

Models and experiments offer us neat narratives that offer only a part of the answer. Blindly accepting research while ignoring the the scope and limitations of the study is the narrative fallacy in full effect, and, by being more skeptical, we are able to better escape the trappings of narratives and have a more nuanced view of a highly complex world. Economics started out as a moral philosophy concerned with the fair distribution of resources. The true rationalism Mises extolled is not found in models but in this exercise of philosophy. That being said, Mises establishes free will is a central assumption in the study of human action, and, by extension, Economics as a whole. This is a narrative as well, again proving that narratives, while never perfect, are necessary. We can only act and make decisions based on narratives. We should at least be aware of the imperfections.

The skepticism surrounding narratives must come with a corresponding optimism surrounding it use.

Breaking Out of the Antechamber of Hope

As mentioned in my definition of what a Black Swan is, some professions rely on positive Black Swans. A writer might need to write a lot to finally get a bestseller, and a scientist might need to do a lot of science to discover something new. These positive Black Swans are something we have limited control over. Luck, as described by NNT, is a great (albeit annoyingly arbitrary) equalizer. Until we get our big break, we are stuck in the "antechamber of hope".

Farming Serendipity: Maximizing (Good) Luck

You can't really influence luck, as per se, but you can increase your exposure to positive Black Swans and limit your exposure to negative ones. NNT describes this as a "barbell" strategy, where you are both hyper-conservative and hyper-aggressive; you limit risk whenever you can in matters where a negative Black Swan can cause catastrophic personal impact, and you expose yourself to high levels of risk in matters where a positive Black Swan can bring unforeseen windfalls.

One application of this is in networking. Networking increases the likelihood of having those serendipitous encounters that can change your life. NNT suggests going for parties, and anecdotally cites the fact that only physically do people really say what they want to say. In a post-Covid world, this advice rings even truer. The lack of physical presence when forming social relationships might have caused a great drop in serendipity that is impossible to quantify. Other than networking, this also applies to those Black Swan-friendly jobs. The more you attempt something, the further you can go. It doesn't scale linearly and you need a good amount of luck to pull anything off, but stopping yourself from trying won't help you.

In fact, this role of luck is key to meritocracy. It's not just about being the best. It's also about working hard enough to be lucky. As the saying goes, God helps those who help themselves. A society emerging from spontaneous order then shares something with God.

The Forgotten Virtue: Minimizing (Bad) Luck

On the other side of the strategy (and this was not emphasized enough in the book), it makes sense to be conservative in terms of your finances and health. Temperance is an often ignored value, but isn't it difficult to find value in temperance when consumerism and excess surrounds many of us constantly? Our entrenched propensity to engage with excess is, taking a page from The Black Swan, a cognitive distortion in how we interpret probabilities. When you don't know when your next meal comes, you would rather eat as much as you can when food becomes available because that's what better guarantees your survival. This rejection of temperance extends to personal finance as well.

Only through this forgotten virtue can we minimize our bad luck. Life is still arbitrary and "unfair", but that doesn't mean we can't have some level of control over it.

Tips & Tricks (circa 3000 B.C.)

So we know that knowledge is decentralized. Does this mean that no one has the answers? I would say that everyone has some part of the answer, and this would include both institutional experts and politically vocal cab drivers. What The Black Swan didn't emphasize was how this applies across time as well. Sure, the ancients didn't really have the same level of scientific understanding of the world, but at the same time, in the great philosophical dialogue from which we get all intellectual disciplines, the collective (and oftentimes contradictory) wisdom of the past thousands of years gives us many partial answers as well.

Engaging with past wisdom with an open mind is critical in making ourselves more knowledgeable. We'll never be able to obtain all the knowledge in the world, but through the skeptical reading of old ideas, we at least have a good starting point for our flawed narratives. We can only act on narratives after all, so we'd better open ourselves up to the knowledge of the past.

The Black Swan has been one of the most enlightening reads of the year so far, and it's likely to feature in my yearly reading recap post. One thing that really struck me is the timelessness of the idea. Black Swans have been present throughout history, and despite all our advancements in technology and information processing, the knowledge problem still remains. We must be skeptical of various sources of knowledge, whether it be experts from academia, talking heads from the media, or that random person you had a conversation with at a bus stop. At the same time, being too skeptical is an easy defense for our own flawed narratives, and we must complement skepticism with an optimistic open-mindedness.

This is the compromise of the skeptic.