From Metal to Myth: Why Modern Money Is Built on Trust

The ability to think in abstractions is among humanity's most distinctive traits, and there is no abstraction, no collective fiction more universal than money. At the dawn of civilization, a numbered piece of paper had no practical use. You can neither eat it nor plant it, and it burns too quickly to fuel a flame. Today, this slip of paper represents an abstraction of value that evokes intense passion—people are willing to work, cheat, or even die for it. How did a string of numbers on a screen come to rule the world?

Money and Prices: What Are They Worth?

Money has three* primary purposes1:

- Medium of exchange: Instead of relying on barter, gifts, or debt, money acts as a recognized intermediary that expedites the trading process.

- Unit of account: Because money is widely recognized, it acts as a standard for valuing goods and services.

- Store of value: Money allows one to transfer value across time by either saving for the future or borrowing for the present.

Through these three main purposes, money translates our shifting, qualitative preferences into a shared standard of value, a language most people can understand. Money is a form of communication, and this signalling function is most evident in the concept of prices.

Prices are the amounts of money transferred from consumers to producers for specific goods, and in mostly free economies they emerge organically through voluntary exchange based on perceived costs and benefits. Without prices, producers lack the signals needed to know what to produce and how much to produce. Considering that supply chains typically consist of multiple exchanges of capital goods before the creation of the final consumer good, this problem propagates to every level and causes widespread inefficiency and misallocation. Consumers also suffer, receiving the wrong goods in the wrong amounts2^.

Outside of economics, money has gained more symbolic roles, often used as a sign of status and a marker of success. In today's meritocratic societies, money is something earned through skill, luck and determination. Unlike under the ancien regimes, much of today's elites need no divine mandate as their wealth largely is earned from some present or past participation in the meritocratic process instead of being bestowed upon them by divine right. The transition from aristocracy to meritocracy is a transition from the age of the nobles to the age of the merchant, and money has become more important than ever.

The Gold Standard and the Monopoly Over Money

Buried Treasures: The Age of Commodity Money

Given the aforementioned purposes of money, the main criteria for something to be considered "money" are that it be durable enough to represent value over time, common enough to be an easily accessible standard of value, and portable enough to be used as a medium of exchange. For millennia, precious metals such as gold and silver were used for coinage, and other forms of so-called commodity money included natural goods such as seashells and cattle3. This is in contrast to today, when gold and other commodities are considered alternative investments and are valued in monetary terms, rather than being money themselves.

So what, then, is money today? Money, in our present understanding, is fiat: the currency we use daily derives its value solely from the authoritative decree of the state, and it is merely this decree, and the trust surrounding it, that gives fiat currencies their value4. How did we get here?

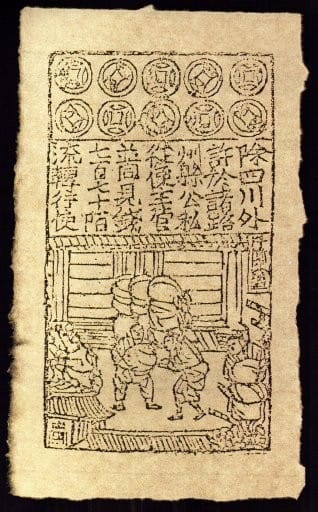

Paper Money: Trust Made Tangible

One problem with gold coins is that it's risky to carry or store substantial amounts of currency. Whether by theft or robbery, a large purse invites crimes you might not want to invest in preventing. Governments and banks, with their far greater resources, are better able to protect your tangible money. Beyond crime, sometimes, it's just too inconvenient to count and carry a large number of coins3. This provided the motivation for a group of merchant enterprises in Song Dynasty Sichuan to create a system of promissory notes (known as jiaozi), often recognized as the first instance of paper money—especially after the state intervened and nationalized the system in 1023, following the bankruptcy of many of those merchant enterprises5.

Paper money, in this conception, represented a promise that the issuer would back its face value with intrinsically valuable goods. The key to this promise is trust. Without this trust, paper money has no more value than its raw materials.

This promise was established across developed economies worldwide, with the last iteration of this promise being the gold standard, in which specific units of gold formed the fundamental units of account. For example, in this system, one United States Dollar represented a specific amount of gold, and users of the USD had to trust that the U.S. government had the gold reserves to back the value, such that the dollar could be freely exchanged for that amount of gold at the central bank. However, this convertibility was not always honored. For example, during both World Wars and the Great Depression, it was suspended across many economies6. Currency wars and volatile exchange rates became normal, stifling international trade and investment7.

The Bretton Woods Agreement: From Representation to Collective Fiction

In July 1944, towards the end of World War II, delegates from 44 Allied nations met in a quaint mountainside resort known as Bretton Woods and agreed on a new financial order that re-established the gold standard, with the catch being that only one country really had to honor it: the United States of America. With two-thirds of the world's gold reserves, the world's largest economy, and considerable trust and goodwill, the United States was the best candidate to forge the monetary order ahead. The agreement was to peg each currency to the U.S. Dollar, while the United States additionally pegged the USD to a fixed amount of gold ($35/ounce). The Bretton Woods Agreement pioneered a globally standardized gold standard that cemented the U.S. dollar's role as the world's reserve currency8.

However, the postwar economic miracles of many countries made one thing clear: the supply of gold could not keep up with the demand for money. The demands of the expanded welfare state (through President Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society program) and external wars (e.g., the Vietnam War) led to massive budget deficits, partially financed through seigniorage—the practice of printing more money to raise revenue9. Slowly, trust was being undermined, and resentment grew over the U.S.'s privilège exorbitant (or "exorbitant privilege").

“It costs only a few cents for the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to produce a $100 bill, but other countries had to pony up $100 of actual goods in order to obtain one.”

— Barry Eichengreen, in "Exorbitant Privilege: The Rise and Fall of the Dollar and the Future of the International monetary system" (2011)

In 1965, French President Charles De Gaulle, doubtful of the Federal Reserve's ability to back the amount of U.S. dollars, started exchanging dollars for gold10. One by one, countries began leaving the Bretton Woods system, starting with West Germany, then followed by Austria, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Switzerland. The clock was ticking, and time was running out9.

On August 15, 1971, U.S. President Richard Nixon issued a shocking proclamation: dollars could no longer be converted into gold. The Bretton Woods Agreement was dead, and the gold standard died along with it9.

The Federal Reserve had by then completed its monopoly over money. Monetary policy became more flexible worldwide, and the supply of money grew significantly. This ushered in a decade of stagflation in the U.S., marked by high inflation, high unemployment, and low economic growth11.

Digital Gold: A Techno-Libertarian's Last Laugh

The curious thing about gold is that its value is a subjective, emergent phenomenon arising from individual preferences, rather than from state decree (fiat). Gold does not need a state to function as currency. While some states might conquer mines and mint coins, history is filled with examples of coins being debased, either by mixing non-precious metals into precious ones or by clipping the edges of coins to make them imperceptibly lighter12. The role of the state in the history of commodity money has had mixed results, at best.

With the transition to paper money and fully fiat currencies, our current monetary system involves floating or pegged currencies, interest or exchange rate management, and adjustments to the money supply. All of these actions stem from a trusted authority: the state. Even the absolute monarchs of old did not possess such a monopoly over money.

"In the absence of the gold standard, there is no way to protect savings from confiscation through inflation. There is no safe store of value."

— Alan Greenspan, Chairman of the Federal Reserve (1987-2006)13

The abandonment of the gold standard was controversial when it was first implemented, and it remains controversial to this day. Pro-interventionist economists view the transition as positive, since it allows governments greater control over the economy through monetary policy6. From a national security perspective, the gold standard can constrain state financing precisely when it is needed most: during wartime.

On the other hand, Austrian school economists view fiat currency as a government distortion of free markets that results in inflation and economic instability14. Many conservatives dislike fiat currency because the inflation that it enables (due to the ability of the central bank to print more money) erodes savings and incentivizes debt accumulation15.

As this controversy continued, money became increasingly global and digitized. As money began traveling farther than ever, a digital system for transferring it became necessary. This requires a trusted intermediary to coordinate the exchange of funds. Trust, the foundational value of currency exchange since the dawn of paper money, became even more paramount. What if you could do without it?

On 31 October, 2008, an anonymous developer, Satoshi Nakamoto, published a paper titled Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System16. In it was a description of how money could be exchanged digitally without a trusted third-party, with verification instead relying on cryptographic proofs. The records of these cryptocurrency exchanges are stored on a distributed ledger known as a blockchain.

Techno-libertarians, who believe that technologies like cryptocurrency can reduce dependence on the state and empower individual freedom, see this as a beginning of a new monetary era. Like gold, Bitcoin has a limited global quantity, is durable (so long as the Internet exists), and is, in principle, independent of government control. While gold's credibility is built on centuries of tradition, Bitcoin's credibility is built on the transparency of its code and blockchain. In a world where gold as a currency looks increasingly obsolete, Bitcoin appears as a digital counterpart that, while having its own problems, offers a glimpse into what decentralized currencies of the future might look like. Techno-libertarians might have the last laugh, or they might merely be celebrating a fleeting, limited wave of social acceptance.

Conclusion: The Future of Money

Will we return to the gold standard, or will Bitcoin, or some other cryptocurrency, overtake gold as a reserve asset? Will growing domestic pressure for American isolationism finally end the current monetary system, and if so, what will replace it? The U.S. dollar remains the world's premier reserve currency, a vestige of the Bretton Woods Agreement. Will it be replaced by a basket of currencies or by something entirely new? The evolution of money will depend on how society's perceptions, not just of money, but also of state intervention in the economy, continue to evolve. One thing is certain: the story of money is, in many ways, the story of trust—and how far it can scale.

* Technically, there is a fourth function: a standard of deferred payment. However, what I've stated is more aligned with what I had learnt as part of my Economics major. For those curious, what this means is that money facilitates the future settlement of transactions.

^ The economic calculation problem (identified by Ludwig von Mises) is distinct from the knowledge problem (identified by Freidrich Hayek), which I had discussed in my essay on The Black Swan (Nassim Nicholas Taleb, 2007)

Disclaimer: The information provided in this essay does not constitute investment, financial, or other professional advice. The content is intended solely for informational and educational purposes. Readers are advised to consult with a licensed financial advisor before making any financial decisions.

- CFI Team, "Functions of Money," Corporate Finance Institute. https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/economics/functions-of-money/ (accessed Jun. 9, 2025)

- Mises, L. v. (1920) "Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth," Mises Institute. Available: https://mises.org/online-book/economic-calculation-socialist-commonwealth (accessed Jun. 9, 2025)

- Bitcoin Magazine. (Oct. 27, 2023) "What is Commodity Money?" Nasdaq. https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/what-is-commodity-money (accessed Jun. 9, 2025)

- Chen, J. (Jul. 02, 2024) "Fiat Money: What It Is, How It Works, Example, Pros & Cons," Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/fiatmoney.asp (accessed Jun. 9, 2025)

- "Song Dynasty Paper Money," Totallyhistory.com. https://totallyhistory.com/song-dynasty-paper-money/ (accessed Jun. 9, 2025)

- Lioudis, N. (Oct. 14, 2024) "What Is the Gold Standard? History and Collapse," Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/09/gold-standard.asp (accessed Jun. 9, 2025)

- Jacks, D.S. and Novy, D. (2020) Trade Blocs and Trade Wars during the Interwar Period. Asian Economic Policy Review, 15: 119-136. https://doi.org/10.1111/aepr.12276

- Chen, J. (Apr. 19, 2025) "Bretton Woods Agreement and the Institutions It Created," Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/brettonwoodsagreement.asp (accessed Jun. 9, 2025)

- Bordo, M. D. (2017) "The Operation and Demise of the Bretton Woods System; 1958 to 1971," Hoover Institution. Economics Working Paper 16116. https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/research/docs/16116-bordo.pdf

- Time. (Feb. 12, 1965) "Money: De Gaulle v. the Dollar," Time. https://time.com/archive/6634666/money-de-gaulle-v-the-dollar/ (accessed Jun. 9, 2025)

- Nielsen, B. (Jun. 27, 2024) "Stagflation in the 1970s," Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/articles/economics/08/1970-stagflation.asp (accessed Jun. 9, 2025)

- APMEX. (Apr. 21, 2025) "What Is Currency Debasement?" APMEX. https://learn.apmex.com/answers/what-is-currency-debasement/ (accessed Jun. 9, 2025)

- Greenspan, A. (1966) "Gold and Economic Freedom," Objectivist. https://constitution.org/1-Activism/mon/greenspan_gold.htm (accessed Jun. 10, 2025)

- Polleit, T. (8 Jun, 2024) "The Achilles Heel of the Fiat Money System," Mises Wire. https://mises.org/mises-wire/achilles-heel-fiat-money-system (accessed Jun. 10, 2025)

- Postel, C. (Sept. 3, 2013) "Why conservatives spin fairytales about the gold standard," Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/world/why-conservatives-spin-fairytales-about-the-gold-standard-idUSBRE98G07F/ (accessed Jun. 10, 2025)

- Rizzo, P. (Oct. 31, 2023) "The Bitcoin White Paper Is Now Officially 15 Years Old," Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/peterizzo/2023/10/31/15-facts-about-the-satoshi-white-paper-on-bitcoins-15th-birthday/ (accessed Jun. 10, 2025)

Figures

- Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, CC BY-SA 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/, via Wikimedia Commons

- John E. Sandrock, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Archives New Zealand from New Zealand, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- voytek pavlik, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons